After a rough day at the office, and knowing that you will be in deep trouble back home because you left your dirty socks on the kitchen table, there was always a comforting thought at the end of the working day. That was to go to what, for many, has become a ‘home away from home’ — Jameson’s in Commissioner Street, Johannesburg.

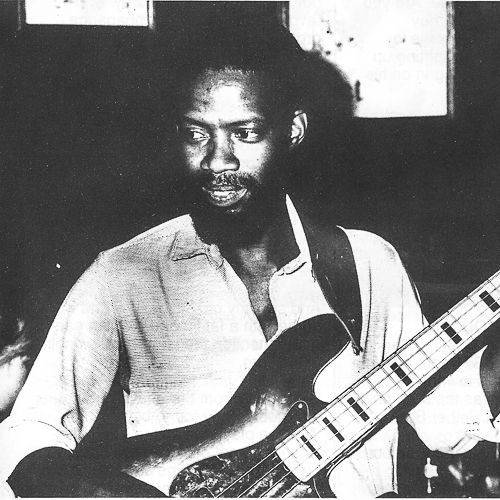

Stepping into this underground bar and restaurant, you could feel the spirit of love and friendship come over you. People of all shapes, sizes and colour would be tapping their feet to the cool music of the resident band. The band-leader and pianist, Dave Lithins, would grab the microphone and announce, “The Preacher on bass!”. And Anthony Saoli would hold the attention of his ‘congregation’ with the ‘sermon’ from his bass guitar. For that magic moment, all the troubles in the world were forgotten.

THE GENTLE GIANT

Now Tony Saoli is no more! He has gone on to join the heavenly band of fellow musicians like Bunny Luthuli and Henry Sithole. He died on the 9th of January.

For two weeks afterwards, Jameson’s was not the same. People walked about in a daze and kept repeating the same question, “Tony! Dead! Are you sure?” Others looked as if they expected to see the man come in pushing his amplifier and lighting up the whole place with a big grin on his friendly face.

For those two weeks there was no live music. Maybe as one musician put it, “The bassists are spooked. No one wants to step into Tony’s boots so soon.”

Or perhaps it was the artists’ show of respect for a gentle, bearded giant with a smile as wide as the ocean, a being who laughed more than he talked.

MUSIC IN THE BLOOD

Tony was born some 37 years ago in the Eastern Transvaal town of Bushbuckridge. He was the sixth child of Jacob Russell and Esther Saoli.

Music was very much in Tony’s blood. His father was a school principal, church elder and organist. Sundays were spent at the church where Tony and his brother Winston would pump the organ pedals at their father’s feet while he played. They pumped until their muscles ached.

A couple of years later, Tony got a little tired of all the pedal pumping. He wanted to sing in the church choir as well. He kept telling his father, “I want to sing in the church choir.” When asked what part he wanted, he replied, “I want to sing bass,” trying to make his voice sound deeper. He got the part.

Old man Saoli also had something of a jazz collection. The boys used to listen to American big names like Paul Chambers and John Coltrane. “But,” Tony once said in an interview, “I didn’t understand what jazz was all about, but we just listened anyway. My favourite then was the mbaqanga group, Makhonatsohle Band.”

THE FIRST TIME

Tony always liked to tell the story of the time he first picked up a guitar. One hot afternoon a rather big fellow in the village stood in the ‘ring centre’, a patch of sandy ground, and challenged anyone to a boxing match. To his horror, the boys pushed Tony into the ring. It was an unwritten agreement that once you were picked to fight, you could not back out.

And so Tony did his best — and went home with a fat lip and swollen ears, not to mention the church bells ringing in his ears.

Still aching from the beating of that afternoon, Tony found big brother Winston playing a guitar. The guitar was made out of a gallon tin flattened out at one end. Strips of car tubes were tied around it for strings. Tony picked up the guitar…and gently stroked a tune.

Soon the pain was forgotten. And there and then Tony decided he was going to become a musician. After all, music healed, boxing hurt. But if Tony had dreams of becoming a musician, his parents had other ideas. His grandfather Anthony, after whom the young man was named, used to be a policeman. And it was into his boots that his parents wanted Tony to step. For once he went against their wishes. As he laughingly recalled, “Ayi! I decided it was not my line.”

A ‘UNIVERSITY’ EDUCATION

1963 saw a change in Tony’s life. His father was transferred to a new job in Johannesburg. The family followed.

After finishing high school in Rockville, Soweto, Tony furthered his studies by correspondence with Damelin. But still he wanted to be a professional musician. So it came as a pleasant surprise when one day his other brother, Chamberlain, bought Tony a guitar.

With the guitar under his arm, Tony went straight to Dorkay House in Eloff Street in downtown Jo’burg. For those of you who don’t know, Dorkay House in its day was one of our greatest ‘universities’ of music and culture.

There he learnt classical guitar under music teacher and trumpeter, Cyril Khumalo. And it was there where two other future giants of South African music found him practising.

Bunny Luthuli and guitarist Sol Malapane had been trying to form a band. All they needed was a bassist. But a good one was hard to find. .And so their search led them to Dorkay House where they found Tony. After the “hoezits”, they sat down to listen to him playing. What they heard told them that their search was over. ‘Drive’ was formed that year. It was 1969.

Only two years later, ‘Drive’ won the first prize in a competition that bands all over the land took part in — and they walked away with the R500 prize money. Tony never forgot how a chap called Gilbert Strauss, who provided the group with transport and instruments, refused to touch a cent of the money. He told the men to divide it among themselves. It was something that was not very common, then or now.

Tony, who even in his saddest moments managed a smile, once said, “The big guns are in this business for the money they can get out of it. Recording studios, radios, managers…you try to play something from inside of you, something meaningful, and they tell you, ‘the public doesn’t like jazz. They won’t buy it.’ And that’s the end of the story.”

THE FULL-TOOTHED SMILE

After Henry and Bunny died in a car accident, the band was no longer the same. Tony did not get along with some members of the group. He left after a show in Cape Town and went to Lesotho where he played with a piano player called Sam.

Tony also made friends with two other ‘muso’s — Tete Mbambisa and Dave Lithins. He spent a lot of time jamming with them too.

Two and a half years later, Tony came back to Johannesburg where he practised with a group in Hillbrow. But not for long. Dave came looking for him. He told Tony he was forming a trio — and was Tony interested in joining? That was in 1984 — and that’s how it stayed until the very end.

When not sitting with the Dave Lithins Trio, Tony played with the soft spoken and respected guitarist, George Mathiba. The two were good friends — and were into their second week of playing at Jameson’s when the news of Tony’s illness came.

George had his guitar ready and waiting when Mike, the bartender, received a call, “Tony is sick and has gone to see a doctor.”

There was nothing to do but wait for the next evening. The following day a neighbour of Tony’s rushed into the Learn and Teach offices. “Hen mfowethu, Tony collapsed yesterday and has been

admitted to Baragwanath,” he said.

A phone call was made to Bara. The news came like a bolt of lightning, “I’m sorry, but Tony Saoli is dead.” Shock, disbelief, and even downright anger. It was the same for everybody who heard it. But it was a fact.

The ‘Preacher’ is gone. Everyone who knew that warm handshake, the gentle backslap and that full-toothed smile will know what we have lost. And they would gladly share our heartfelt message of condolence to his loving wife, Kebogile, and their two lovely children.

And so the time has come to let ‘The Preacher’ rest in peace. Your sermon will be forever in the hearts of those who listened to it. Farewell, my friend!

Comments